Child protection report lacks crucial national detail on abuse in out-of-home care

Author: Dr Katherine McFarlane

Publication Date: Tuesday, 13 Mar 2018

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare has released a new report showing that one in 32 Australian children received child protection services in 2016-17, with 74% being repeat clients.

The report also noted that the number of children receiving child protection services rose by about 25% over five years, which may “relate to changes in the underlying rate of child abuse and neglect, increases in notifications, and access to services, or a combination of these factors.”

It follows the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse’s final report, which included 409 recommendations to make institutions safer places for children.

One of the Commission’s most striking findings was that Australia’s alternate care systems cannot protect children from abuse.

Today’s Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) report, titled Child Protection 2016-2017, reinforces that some fundamental changes are needed to redress this situation.

What’s in today’s report - and what’s not?

The report notes that in 2016–17, the national recurrent expenditure on child protection and out-of-home care services was $4.3 billion, up 8% from 2015–16.

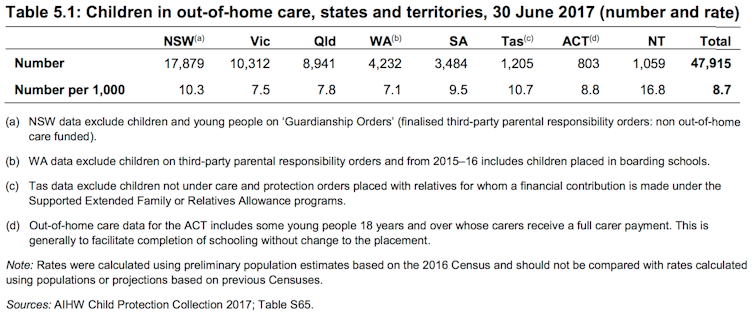

A significant proportion of this money went to provide alternate care to the 47,915 children (as of June 2017) who were in out-of-home care. These are children who cannot live with their families because of abuse or neglect, parental incapacitation or illness.

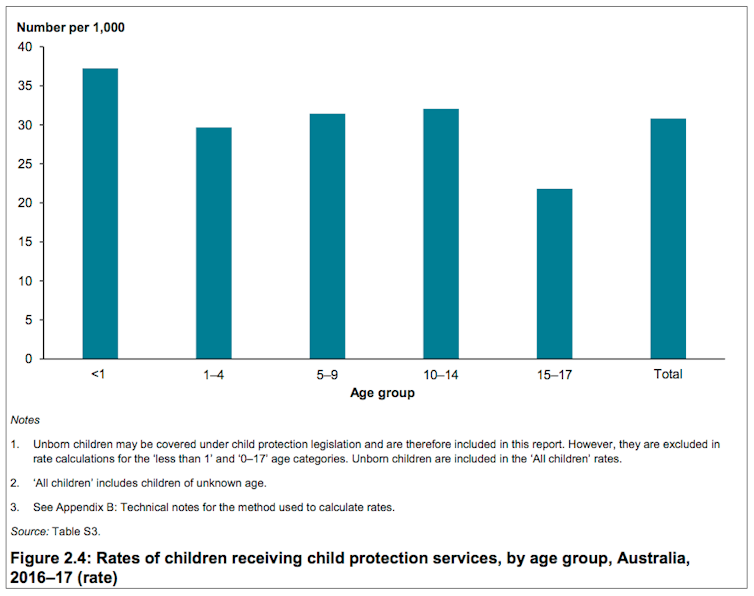

These children are mostly young and highly vulnerable. The AIHW report noted that across Australia in 2016–17, infants were most likely to have received child protection services, while those aged 15–17 were least likely. The median age of children receiving services was eight.

The rates are higher for Indigenous children, who are in out-of-home care at a rate of 13.6 per 1,000. In 2016-17, Indigenous children were also 10 times as likely as non-Indigenous children to enter out-of-home care.

Many children have already spent considerable periods living away from their families: for example, 41% of children in out-of-home care have been there for five years or more.

For the first time, AIHW presented data on disability status. While national figures aren’t available and definitions aren’t consistent, the report said:

In 2016–17, data on the disability status of children in out-of-home care were available for six jurisdictions, representing 71% of children in out-of-home care at 30 June 2017. Overall, 15% of children in out-of-home care at 30 June 2017 were reported as having a disability.

It’s a lot of data to get your head around. Yet amidst all the statistics, tables and figures, one crucial measure for benchmarking, identifying and acting on child abuse is missing.

There is no reliable national data in this report on the number of notifications, investigations and substantiations of abuse that takes place when a child is in out-of-home care.

The report says that:

Some jurisdictions include cases of alleged abuse in out-of-home care in the data provided for this report on the number of notifications, investigations and substantiations… but these cases cannot be separately identified in the national data.

Without this basic information on the national rate, government assurances that children are safe in out-of-home care ring hollow.

Abuse of children in out-of-home care

The Royal Commission noted that a range of factors allow perpetrators to exploit opportunities to abuse vulnerable children in care. These include separation from family, unstable placements, isolation and a lack of relationships with reliable, safe adults.

It made over 30 recommendations aimed at improving Australia’s out-of-home care system so that children are less likely to be sexually abused while they are under the state’s protection.

Significantly, it recommended that federal and state governments collect information about children who were found to have been sexually abused while in out-of-home care, as well as information about their characteristics and the alleged abuse.

It also recommended the establishment of a nationally consistent approach to service delivery, recording, reporting, and information sharing for child sexual abuse in out-of-home care.

Today’s AIHW report cautions that national child protection data are likely to understate the true prevalence of child abuse and neglect across the country.

Its own figures, which only include notifications made to organisations like the police and non-government welfare agencies if the notifications were also referred to child protection department, support this assertion.

However, the lack of data in the AIHW report relating to abuse in out-of-home care also reveals a more troubling aspect of our national child protection systems.

The Royal Commission is the latest body to have found that children in out-of-home care have experienced abuse at the hands of people meant to protect them. Numerous inquiries have made similar findings. In 2009, the prime minister apologised to people abused as children in out-of-home care.

It’s not just historical abuse, as a series of inquiries instigated since the National Apology have made clear.

Children living in group home settings (also known as residential care) appear to be the most vulnerable.

The failure of government departments and welfare agencies to report data on the abuse of children in care allows those bodies to escape scrutiny.

National data collection and public reporting by state and territories of their performance may seem a minor issue. But as the Royal Commission has made clear, it is only through having this information that we will be able to learn the lessons of the past, and ensure that we have measures to keep safe the children we have placed under government care and protection.

ends

Media contact: Dr Katherine McFarlane ,

Media Note:

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.