Good, bad and ugly for Antarctic penguins

Author: Wes Ward

Publication Date: Wednesday, 7 May 2014

Charles Sturt University (CSU) ecologists Dr Melanie Massaro and Dr Alison Matthews were part of a team of scientists in the Antarctic last season studying the effects of climate change on the Adélie penguin, one of Antarctica's truly 'local' penguins. Over the last 20 to 30 years, as temperatures in the Antarctic have increased, Adélie penguin numbers on the Antarctic Peninsula have declined as the birds move further south. But there is only so far south they can go ...

The

scenes are stunningly beautiful: blue skies against the contrasting white of

the Antarctic landscape; wildlife shots that equal those you would expect to

see in a David Attenborough documentary; snow covered hills and mountains that

blend with a frozen sea.

The

scenes are stunningly beautiful: blue skies against the contrasting white of

the Antarctic landscape; wildlife shots that equal those you would expect to

see in a David Attenborough documentary; snow covered hills and mountains that

blend with a frozen sea.

And then there are other images: tents struggling to remain upright in 145 kph winds; brown sludge flowing from the so-called 'rivers of filth'; a penguin caught in the jaws of a leopard seal; the bodies of mummified penguins.

Arriving in splendour

Dr Melanie Massaro's most recent visit in January 2014 was her 12th visit to Antarctica, but for Dr Alison Matthews it was her first. Both ecologists are members of CSU's Institute for Land, Water and Society and School of Environmental Sciences.

Dr Matthews, who has a passion for snow, skiing, the cold and mountains, had always wanted to go to the Antarctic so she "couldn't possibly pass up the opportunity" when she was invited by Dr Massaro to be a member of a research team studying Adélie penguins at Cape Crozier on Ross Island.

"Just getting there with the US Airforce in a Hercules LC130 was pretty exciting," Dr Matthews says.

"I woke up early the morning we were due to fly out and couldn't get back to sleep. I felt like a little kid. My first glimpse of the Antarctic from the plane's window was pretty amazing. It's just such a spectacular place. And then Cape Crozier is such a special place right next to the Ross Ice Shelf. Not many people get to go there."

The two spent a week at the US McMurdo Station on Ross Island where Dr Matthews completed a number of courses including survival training. While in McMurdo station they took the opportunity to visit the historical Discovery Hut, erected by Captain Scott's team in 1902, before being flown by helicopter to Cape Crozier

Hooked on Antarctica

Dr

Massaro first went to the Antarctic in 1998 as a lecturing scientist for a

Canadian tour company which specialises in expedition cruises to the Antarctic.

Dr

Massaro first went to the Antarctic in 1998 as a lecturing scientist for a

Canadian tour company which specialises in expedition cruises to the Antarctic.

"That really hooked me to the Southern Hemisphere and Antarctica," recalls Dr Massaro, who continued leading and lecturing on Antarctic cruises every summer until 2007 when she made the trip for the first time as a researcher.

Since 2009, she has been part of a multi-national team, including researchers from the US, New Zealand and France studying Adélie penguins in the southern Ross Sea. While the New Zealand researchers study the penguins at Cape Bird, the American team conducts research at Cape Crozier and Cape Royds, where the most southern colonies of Adélie penguins are located.

Banding international efforts

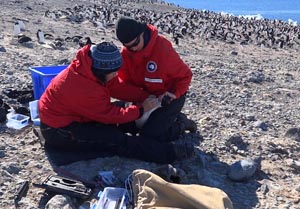

"The big, overall project is a meta-population study trying to figure out climate change effects on Adélie penguins," says Dr Massaro. "My part of the project focuses on how penguins may respond to challenging environmental conditions by studying penguin physiology."

To do this the researchers attached devices called accelerometers to known-age penguins, with the oldest birds being 17 years old. To follow individual birds through their life, researchers have banded several thousand birds since 1996.

"But only a small percentage of them return," says Dr Massaro. "At Cape Crozier we would encounter about 1 000 banded birds per season among this big colony of 200 000 pairs."

Not quite like 'looking for a needle in a haystack', but almost.

"It takes quite a lot searching to find these banded birds but we do have the GPS coordinates of their nests from previous year," says Dr Massaro. "The birds tend to return to a similar area where they nested previously so we go back there looking for them."

The challenge of life

Finding the banded birds isn't the only challenge. Cape Crozier is one of the windiest places on Ross Island with constant winds that can get up to 145 kph; a penguin colony of 200 000 birds is a very smelly place to work in; living conditions are fairly rudimentary; and working hours are long and occasionally stressful.

The one hut serves as a simple laboratory, a kitchen and living area and a communication centre for the team of six. However, each team member did have their own tent to sleep in at night – the same kind of tent that Scott used for his Antarctic expeditions 100 years ago.

"At the base of the tent there is this little skirt that you have to pile rocks on to keep it secure," says Dr Matthews. Her tent didn't blow away but she admits that on her first night at Crozier when the wind came up at 1 am and she hadn't worked out how to close the door flap, it was a bit unnerving.

As the aim is to have as minimal an impact on the environment as possible, all of the team's waste needs to be carried off site, so no one showers for five weeks. They melted glacial ice for water. And then there are the 'rivers of filth'.

Rivers of filth

"Decomposition in the Antarctica is slowed down," says Dr Massaro. "There is no soil as such. It's volcanic rock and the only organic matter that comes into the system is penguin poo and dead penguins. Over 100s of years the dead penguins and the guano pile up mixed with pebbles and rocks. You see mummified penguins everywhere."

As she says, that's fine for 10 months of the year when everything is frozen solid. "It smells like a usual seabird colony which isn't so bad," says Dr Massaro. But when the temperature increases to above 0 degrees Celsius, decomposition starts.

"As the glacier melts, these 'rivers of filth' start flowing and defreeze all these carcasses and guano; it's the most disgusting thing because the river is full of penguin bodies. It's shocking," says Dr Massaro.

And incredibly smelly. Penguin colonies in the Antarctica, unlike other seabird colonies, don't have invertebrates or insects to help speed up the decomposition process.

"But that didn't worry me at all," says Dr Matthews. "I've worked with lots of different animals that are very smelly; it's part of what we do."

Gathering

data

Gathering

data

After the accelerometers are attached to the penguins they are returned to their nests and chicks. When the birds' partners return, the ones with the device then go out to sea for several days to find food for their young. When they return, the devices are removed.

"The device gives us detailed information on how much and far the penguin moves; how deep they dive and how many dives they do; and how much energy they use," says Dr Massaro.

The researchers also take a blood sample "which tells us all sorts of things but mainly we are looking at corticosterone levels, which is a stress hormone". When the chicks are bigger and begin to moult they are banded.

Gathering signs

Other

scientists have found Adélie penguins are moving south.

Other

scientists have found Adélie penguins are moving south.

"There used to be colonies of Adélie penguins on the Antarctic Peninsula [the most northern part of Antarctica] but they are moving south," says Dr Massaro, "but our penguins are at the southern- most colony, so they can't go any further south."

The warming effects of climate change are still impacting the Ross Island penguins. Huge icebergs are breaking off the Ross Ice Shelf and these giants of glacial ice block off McMurdo Sound.

"This affects our colonies as the penguins can't return to some of their colonies anymore," says Dr Massaro. Adélie penguins migrate each winter. When the Ross Sea near their breeding colonies freezes they migrate north to the edge of the sea ice.

"The Cape Royds colony had a big crash several years ago. There used to be over 4 000 pairs and now there are only about 1 600 pairs."

Dr Massaro says it is still too early to draw conclusions from her project regarding stress levels.

"It's hard to tease apart climate change effects from other factors influencing the penguins," she says.

Other factors?

"We do know the penguins at Cape Crozier are struggling to raise their chicks," said Dr Massaro.

"For some reason there may not be enough food in the ocean where they feed which may be linked to human activities such as climate change, which can change prey abundance and distribution; or it might be because of competition as the Crozier colony is very large and the penguins are depleting their resources. We've found that they start depleting their resources close to the colony and then they have to move further and further afield to forage for food as the season progresses."

This lack of resources may also explain why the penguin chicks at Cape Crozier are small, unlike the "huge, fat chicks" at the much smaller colony at Cape Royds.

"Cape Royds is the riskier place to be at the beginning of the season because the adults really have to work hard to get to the colony because of the extended sea-ice early in the season. But once the adults survive the incubation period and the ice breaks up, Cape Royds is the better place for raising big healthy chicks," Dr Massaro says.

Dr Massaro isn't planning to go back to Antarctica next season because of other commitments (she has two new PhD students) but can't envisage staying away for long.

"I would love to go back and take my husband there," says Dr Matthews. "It's such a fabulous place."

ends

Editor's note:

Of German and Italian parentage Dr Melanie Massaro is an evolutionary and behavioural ecologist and ornithologist who joined CSUs School of Environmental Science in February 2013 as a lecturer. Dr Massaro did her undergraduate studies at the Ernst-Moritz-Arndt University and the University of Kiel in Germany before going on to do her Masters of Science at Memorial University of Newfoundland in Canada on Northern hemisphere seabirds. In 2004, she completed her PhD at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, on Yellow-eyed penguins and Snares penguins which breed on New Zealand's South Island and sub-Antarctic islands.Her post-doctoral research focussed on highly endangered species, such as the black robin. Currently she is part of a team researching "Effects of climate variability on Adélie penguins in Antarctica" funded by the US National Science Foundation and the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

Dr Alison Matthew, a wildlife ecologist with a Bachelor of Science (Honours) from the University of Sydney, worked for NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service where much of her research was aimed at recovery programs for threatened fauna, wildlife management plans and restoration of degraded habitats on private lands and reserved areas. In 2005 she moved to Albury and CSU on a two year secondment from the Service to teach in the Parks degree before doing her PhD on "Climate change influences on the distribution and resource use of Common Wombats in the Snowy Mountains, Australia" which she completed in 2011. She has since worked as a lecturer with the School of Environmental Science. She is currently analysing blood samples collected while in Antarctica before she heads off to travel and cycle overseas.

These adventurers shared their six-week experience with a seminar presentation at CSU in Albury-Wodonga in March 2014 entitled "The good, the bad and the ugly side of conducting penguin research in Antarctica".

ends

Media contact: Wes Ward, 0417 125 795

Media Note:

Contact CSU Media to arrange interviews with Dr Melanie Massaro, who is based in Albury.