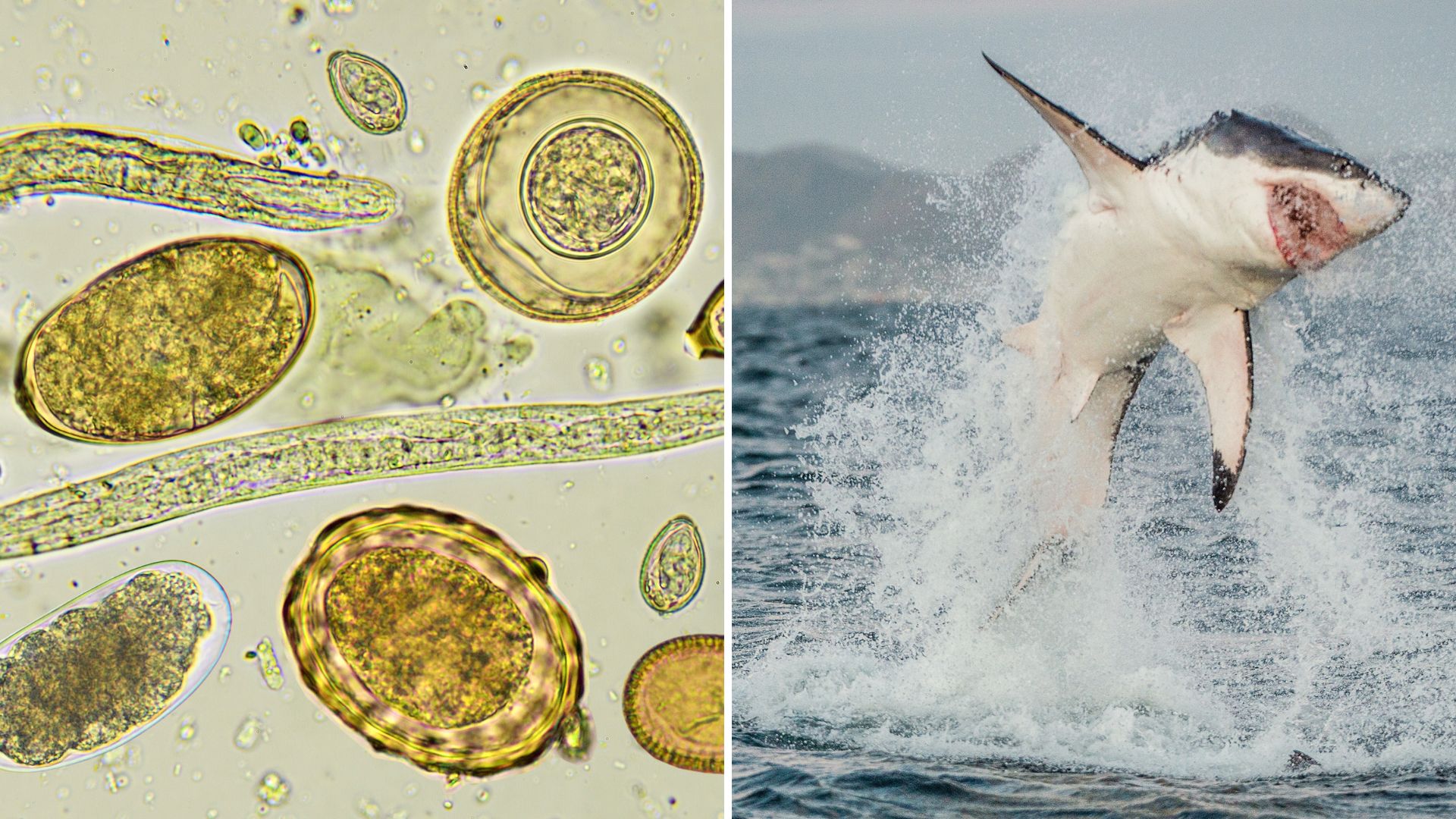

- A new study by Charles Sturt University researchers brings together decades of scattered records on great white shark parasites

- The study reveals significant knowledge gaps in the biology of great white shark parasites and outlines a new research agenda to address these gaps

- Parasites are not villains; they are storytellers, revealing pollution, prey and predator stress, and the pressures facing marine ecosystems

A world-first study by Charles Sturt University researchers has revealed a startling truth about great white sharks – for one of the most celebrated apex predators on Earth, we know little about their parasites or internal ecosystems.

A global scientific review by a research team in the Charles Sturt School of Agricultural, Environmental and Veterinary Sciences and the Gulbali Institute for Agriculture Water and Environment found at least 116 parasites in great white sharks.

The research by Professor in Veterinary Parasitology Shokoofeh Shamsi and co-researcher and Adjunct Lecturer in parasitology Associate Professor Diane Barton conducted the most extensive review to-date, combining scientific literature and museum specimens.

Their study, ‘How much do we know about the parasites of great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) and why they matter?’, is published in the International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife (vol. 28, December 2025).

Professor Shokoofeh Shamsi said this work synthesises evidence from around the world, including records from the USA, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia as well as global museum collections (Smithsonian, Australian Helminthological Collection, EEB Biodiversity Research Collections).

“This global mapping shows enormous blind spots, vast regions with no parasite data at all, despite the great white sharks’ worldwide range,” Professor Shamsi said.

“Our study identified at least 116 recorded parasites in great white sharks ─ mostly tapeworms (cestodes) and copepods ─ though many of these were repeat findings of the same species, yet nearly all research to date is purely descriptive.

“We have next to no understanding of how these organisms influence shark health, energy use, decision-making, behaviour, susceptibility to stress, or even patterns we assume to be ‘attacks’. In other words, we are looking at sharks and seeing only the surface.”

Professor Shamsi said protecting great white sharks requires understanding the unseen biological forces that shape them, including how parasites and other environmental pressures may influence their health and behaviour.

She emphasised that while there is no evidence linking parasites to shark–human interactions, it is important to consider how human activities, such as pollution or microbial change in coastal waters, could subtly affect marine wildlife over time.

“The biggest discoveries about great white sharks may lie in what we have never studied ─ their parasites and microbiome,” she said.

“Parasites provide early warnings about ecosystem stress, pollution and shifting food webs.

“Human activities on land directly influence the health of marine predators and this is why Charles Sturt University regional researchers play a national role in marine conservation, despite being inland.”

Research colleague and co-author Professor Barton highlighted the pivotal role that museum collections play in modern marine science.

She noted that these collections, combined with non-lethal research tools, allow scientists to study vulnerable species ethically and in far greater detail than ever before.

“Museum collections preserve irreplaceable biological material,” she said.

“They allow us to revisit specimens with new technologies and uncover insights that were impossible to detect when the samples were first collected.”

“Healthy oceans depend on recognising the small things, like the hidden architecture of parasites and microbes.”

Professor Shamsi said although most Charles Sturt University campuses are situated inland, that inland perspective gives us a unique view such that our research footprint reaches the coast and ocean every day.

“What happens on land does not stay on land, it travels through waterways, food webs and ultimately shapes the health of marine giants like great white sharks. Our research helps reveal those hidden connections,” she said.

Professor Shamsi said Charles Sturt scientists study how activities on land travel downstream, influencing estuaries, reefs and even the health of marine giants like great white sharks.

“Being inland sharpens our perspective; we see clearly how rivers, paddocks and catchments connect to ocean wildlife,” she said.

“This review reinforces the University’s leadership in integrated environmental science, connecting land to sea, and humans to the ecosystems that sustain them.

“Our inland vantage point is a strength. We can clearly see how upstream human activities ripple into marine life. That is why integrated science matters.”

An important consideration the researchers emphasise is that at the same time, human activities are reshaping the ocean at unprecedented speed, with pesticides, pollutants and land-based pathogens being washed into coastal waters, moving through food webs and reaching apex predators.

They say parasites act as sentinels of these changes, revealing when ecosystems are stressed or breaking down, so studying shark parasites is therefore not just about sharks; it is a way of diagnosing the health of the entire ocean.

The researchers argue that sharks are shaped by more than muscle and instinct. They posit ‘What if part of a shark’s behaviour, including unexpected encounters with humans, is influenced by factors we’ve never measured?’.

“We do not yet know and that is precisely why this research is crucial,” Professor Shamsi said.

“Great white sharks are extraordinary animals and global icons but even they are not immune to the microscopic world and the hidden communities living inside them ─ parasites, microbes, and other symbionts ─ remain almost unknown.

“These microscopic inhabitants can influence energy levels, stress responses, feeding behaviour, and decision-making in other species.

“By studying their parasites and microbiome, we uncover silent forces that may influence their behaviour, resilience and ecological role.”

The researchers emphasise that parasites are not villains; they are storytellers, revealing pollution, prey stress and the pressures facing marine ecosystems, and ignoring them leaves conservation incomplete, a point even major shark research collections have missed entirely.

“A recent volume, White Sharks Global: Proceedings and Recent Advances in White Shark Ecology and Conservation, contained no chapters on parasites or microbiomes,” Professor Shamsi said.

“Their complete absence underscores the depth of this blind spot, and is why our review is a timely corrective, the first step toward understanding the invisible layers of biology that may shape great white shark health, behaviour, and long-term survival.”

Social

Explore the world of social