- Research by a Charles Sturt University honours student and colleaguesindicates that dancing behaviour is more common in cockatoos than previously thought

- Cockatoo dance behaviour is varied and complex, suggesting well-developed cognitive and emotional processes

- Playing music to parrots may provide a useful approach to enrich their lives in captivity, with positive effects on their welfare.

A recently published study by a Charles Sturt University honours student and colleagues reveals more about parrots’ and cockatoos’ highly developed cognitive capacity and indicates that playing them music may improve their welfare.

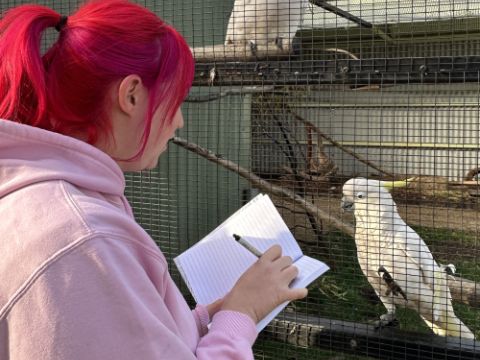

In 2024, Ms Natasha (Tash) Lubke, a Bachelor of Animal Science (Honours) student in the Charles Sturt School of Agricultural, Environmental and Veterinary Sciences undertook a research project examining dancing behaviour in cockatoos (Cacatuidae).

Ms Lubke said parrots are a popular, long-lived companion animal (pet) renowned for their intelligence and problem solving. Many owners report that parrots often dance in response to music and appear to ‘enjoy’ dancing.

“By analysing dance behaviour of cockatoos from 45 YouTube videos as well as cockatoos at Wagga Wagga Zoo and Aviary, I showed that dancing behaviour is more common in cockatoos than previously thought and was seen in 10 of the 21 cockatoo species,” Ms Lubke said.

“My analysis also indicated that dancing is far more complex and varied than previously thought, recording 30 different movements seen in multiple birds and a further 17 movements that were seen in only one bird.”

Ms Lubke said by showing that dancing by cockatoos is not only seen in birds kept in people’s homes but is seen in zoo birds suggests that birds find dancing intrinsically rewarding and/or pleasurable.

“The finding that dancing in cockatoos is seen in many birds, and that dance behaviour is more varied and complex than previously thought, supports the anecdotal belief that these parrots can experience pleasure and enjoy dancing,” she said.

“As well as supporting the presence of positive emotions in birds and advancing dance behaviour as an excellent model to study parrot emotions, the work suggests that playing music to parrots may provide a useful approach to enrich their lives in captivity, with positive effects on their welfare.”

Ms Lubke’s research was supervised by Professor in Animal Behaviour and Welfare Raf Freire and Associate Professor Melanie Massaro, both in the Charles Sturt School of Agricultural, Environmental and Veterinary Sciences, and by UK expert in animal play behaviour Dr Suzanne Held in the University of Bristol School of Veterinary Sciences.

Ms Lubke’s research was supervised by Professor in Animal Behaviour and Welfare Raf Freire and Associate Professor Melanie Massaro, both in the Charles Sturt School of Agricultural, Environmental and Veterinary Sciences, and by UK expert in animal play behaviour Dr Suzanne Held in the University of Bristol School of Veterinary Sciences.

The research paper, ‘Dance behaviour in cockatoos: implications for cognitive processes and welfare’, was recently published in the highly respected PLOS One multidisciplinary journal.

Professor Freire said dancing behaviour in cockatoos is common, varied and appears to arise spontaneously as a pleasurable activity.

“The similarities with human dancing make it hard to argue against well-developed cognitive and emotional processes in parrots, and playing music to parrots may improve their welfare,” he said.

“Further research would be beneficial to determine if music can trigger dance in captive birds and serve as a form of environmental enrichment.”

The researchers caution that keeping parrots as ‘pets’ is a demanding experience and requires significant time and dedication, as well as specialised care and a suitable environment to ensure their welfare.

“Before deciding to care for a parrot, carefully consider if you can meet their complex needs and are able to provide for their long-term care,” Ms Lubke said.

Find out more information about studying the Bachelor of Animal Science, the Bachelor of Equine Science, the Bachelor of Veterinary Technology and the double-degree Bachelor of Veterinary Biology/Bachelor of Veterinary Science at Charles Sturt University.

Social

Explore the world of social