- A study by a Charles Sturt University philosophy academic explores how we make sense of the process by which speculative conspiracy theories are either awarded official theory status or are rejected

- The study challenges the notion that all conspiracy theories are inherently flawed and delves into the origins of theories that invoke conspiracies and are now regarded as official theories

- The research sheds light on the complexities surrounding conspiracy theories and calls for a re-evaluation of the ‘generalist’ approach and concludes that ‘generalism’ should be rejected in favour of ‘non-generalism’

A Charles Sturt University philosophy academic challenges how ‘conspiracy theories’ are commonly thought of, defined and espoused in a recently published journal article.

The paper by Professor Stephen Clarke, ‘When conspiracy theorists win’ (July 2024) is published online in Inquiry, a leading interdisciplinary journal of philosophy.

Professor Clarke (pictured inset at top) is Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Master of Ethics and Legal Studies in the Charles Sturt School of Social Work and Arts.

In his article he asks how we make sense of the process by which speculative conspiracy theories either acquire sufficient evidential support to become worthy of being awarded official theory status, or come to be rejected, in societies in which the epistemic processes by which theories are awarded official theory status function properly.

(Epistemology = the theory of knowledge; epistemic = about knowledge.)

Professor Clarke examined the epistemic defects associated with conspiracy theories and their impact on generalists’ understanding.

He explains that a ‘generalist’ is a term of art in the philosophy literature on conspiracy theories used to refer to everyone who thinks there is some general epistemic defect shared by conspiracy theories.

“Most people are unthinkingly generalists because most people use the term ‘conspiracy theory’ dismissively as in ‘that’s just a conspiracy theory’, insinuating that there must be something wrong with conspiracy theories,” Professor Clarke said.

“The problem is that it is notoriously difficult to find an epistemic defect that is common to all conspiracy theories. Some people try to finesse the problem by using the term ‘conspiracy theory’ just to refer to theories that invoke conspiracies that are also defective theories.

“I’m attacking this argumentative move in the paper by arguing that currently respectable theories that invoke conspiracies started out as theories that were dismissed as ‘just conspiracy theories’.”

The opposite of a generalist is an anti-generalist (like Professor Clarke), sometimes referred to as a ‘particularist’, who thinks that there is nothing special about conspiracy theories as a class and that they ought to be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

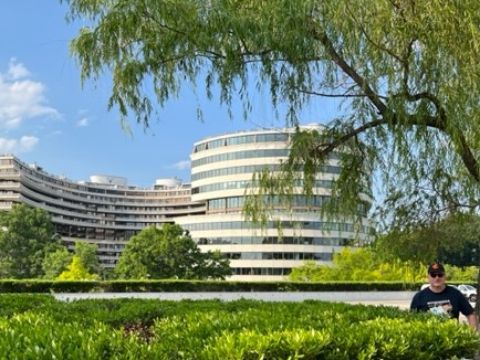

Professor Clarke’s study challenges the notion that all conspiracy theories are inherently flawed, highlighting well-confirmed theories that invoke conspiracies, such as the Watergate theory, as a significant concern for generalists.

“The research delves into the origins of theories that invoke conspiracies and are now regarded as official theories,” he said.

“The study finds that these theories, including the Watergate theory and the ‘false flag theory’, of the Mountain Meadows massacre of 1857 in Utah, USA, initially emerged as mere speculative conspiracy theories.

“Despite attempts to demonstrate otherwise, none of the examined theories were able to prove that they were never mere conspiracy theories, and the findings raise important questions about how generalists should respond to this state-of-affairs.”

Generalists, Professor Clarke asserts, often adopt pejorative definitions of the term ‘conspiracy theory’ and deny that theories invoking conspiracies, which are now regarded as official, ever fell into the category of conspiracy theories.

Generalists, Professor Clarke asserts, often adopt pejorative definitions of the term ‘conspiracy theory’ and deny that theories invoking conspiracies, which are now regarded as official, ever fell into the category of conspiracy theories.

The study explores alternative responses, including breaking with received opinion and denying the existence of any theories invoking conspiracies that can be considered true.

However, this response seems unpromising given the abundance of evidence supporting theories such as the Watergate theory and the ‘false flag’ theory.

Another potential response is to identify special epistemic virtues that some conspiracy theories possess, which could compensate for the epistemic defects associated with the entire class of conspiracy theories.

“However, the study suggests that it is challenging to determine what these special epistemic virtues might be,” Professor Clarke said.

“Early versions of the ‘false flag theory’, now regarded as true, do not appear to possess any more virtues than other speculative false flag theories that are commonly dismissed due to their lack of warrant.”

The study also explores the possibility of defining the term ‘conspiracy theory’ as time-slices of instances of a type of theory, referring to those times when theories invoking conspiracies have yet to accumulate sufficient evidence to be considered worthy of official theory status.

“However, this approach has not been widely adopted by generalists as it would prevent them from dismissing conspiracy theories outright,” he said.

“In addition, theory comparison is not as simple as determining which theory accumulates sufficient evidence first.”

In contrast, non-generalists do not differentiate between mere conspiracy theories and theories that are warranted in belief and invoke conspiracies. This perspective allows for a more comprehensive understanding of cases where mere conspiracy theories evolve into theories that are warranted in belief. The study concludes that generalism should be rejected in favour of non-generalism.

The research sheds light on the complexities surrounding conspiracy theories and calls for a re-evaluation of generalists’ approach.

“As further research is conducted, it is hoped that a deeper understanding of the epistemic defects associated with conspiracy theories will emerge, leading to more informed discussions and interpretations,” Professor Clarke said.

Professor Stephen Clarke works on a range of topics in bioethics, such as conscientious objection, voluntary assisted dying and the ethics of human enhancement, as well as topics in applied philosophy regarding religious extremism, religious violence and conspiracy theories.

Social

Explore the world of social