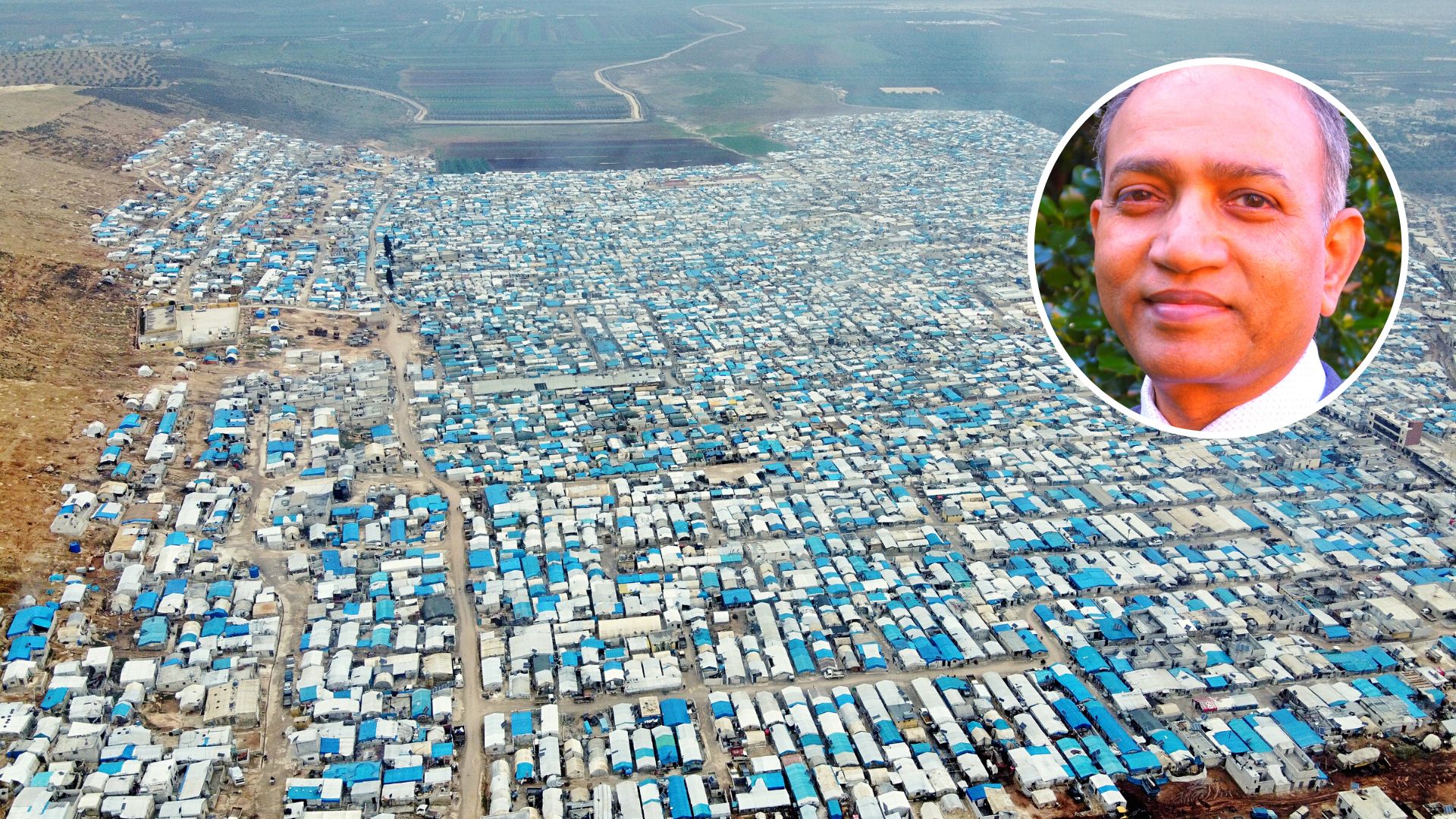

By Professor in Social Work, Manohar Pawar (pictured, inset) in the Charles Sturt School of Social Work and Arts. Professor Pawar is President of the International Consortium for Social Development (ICSD) and is the first non-US citizen to hold the position. He is also a member of the Charles Sturt Institute for Land, Water and Society (ILWS).

According to the United Nations (UN), the number of people in need of humanitarian aid has increased from one in 45 a year ago to one in 33 in 2021.

The UN estimate suggests that 235 million people globally need humanitarian assistance and protection.

To assist just 160 million people, US$39 billion is needed, but as of November 2020, donor nations have offered less than half of that, only approximately US$17 billion.

Globally, this is an extremely serious situation. Uprooted, homeless and on the distressed move, they cannot fight for the basic means for their bare survival – water, food, shelter. They are so vulnerable!

This World Humanitarian Day is the time to remember these millions of vulnerable people in 56 countries, particularly, children, women, the elderly and the sick, and think about their plight, their dignity and worth, their human rights and our respect for them.

Equally important are aid workers, who have been selflessly committing their lives to organise and provide basic services to millions of people to alleviate their misery under uncertain circumstances and unknown futures.

In what way can we translate our respect into action that alleviates humanitarian crises and recognises aid workers’ critical contributions?

Towards addressing this question, it is critical to understand and attack the causes of humanitarian crises.

Drawing from the World Bank analysis presented in the ‘Poverty and shared responsibility 2020: Reversals of Fortune’, I argue that humanitarian crises are caused by three ‘C’ factors.

One of them is climate change and the other two are conflict, including armed conflict, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

In some respects, these ‘Cs’ can be or are interconnected. Climate change issues, for example, the ways of control and use of natural resources such as land, water, fossil fuels and forests, have led and are leading to conflicts ─ political, peaceful and violent.

There is also unequal distribution of resources to adapt and cope with the consequences of climate change.

Generally, those developed countries, which contribute more to climate change are better resourced than those that bear the impact of the climate change in developing poor countries, including land-locked and island sates, which seem to contribute least to the climate change.

Production and use of arms cause climate change as well. It has also been argued that the COVID-19 is due to human interference with natural ecological systems.

There are also conflicting responses to deal the with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Overall, these three ‘C’ factors – climate change, conflict, and the COVID-19 pandemic ─ have culminated to produce huge mass-humanitarian crises in some countries and pockets, including developed countries. Recent famines, floods and fires in Africa, America, Europe, Asia and Australia are a case in point.

The UN states that to mitigate and adapt to these and similar climate change consequences, developed countries have pledged, a decade ago, US$100 billion annually for developing countries.

But that pledge has neither manifested nor fructified so far, nor the universal pledge to achieve net zero emissions by the set target date.

A recently released report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis AR6-WG1) claims with confidence the evidence that human-caused climate change is occurring.

Already people are witnessing and experiencing intensity of climate and weather extremes, whether it is heat waves, droughts, desertification, floods, fires and land degradation.

It appears already irreversible damage has been done and nationally determined contributions are insufficient to reduce the pace of climate change as per the set targets.

As these disaster events are most likely to intensify and increase, so are humanitarian crises in many countries and regions.

There is an urgent need to globally act now on both climate change mitigation and adaptation in all countries, and particularly to aid poor people in developing countries who are most vulnerable, with least resilience and capacity to cope with the impacts of climate change.

Many developed nations have followed the paths of extreme exploitation of natural resources, increasing their gross domestic product (GDP), rapid urbanisation, and over-consumption of goods without any remorse, and they have preached to the world to follow such an unsustainable path as a model for development.

They are therefore morally and ethically responsible to contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies, programs and provisions throughout the world, particularly to poor countries and vulnerable population groups in all countries which have been caught in humanitarian crises.

As part of observing World Humanitarian Day, this appeal and demand is not only reasonable, fair and just from the human rights perspective, but also from a ‘neoliberal ideology’, or the principle of ‘user or polluter pays the price’.

One way of respecting human dignity and the worth of people in the midst of humanitarian crises, and honouring aid workers, is to collectively pursue world protagonists to meet their pledge by releasing US$100 billion annually so that aid agencies and workers can work with more than 235 million people needing humanitarian assistance and protection right now.

Social

Explore the world of social