By Dr Gavin Buzza, Lecturer in Exercise Science and Clinical Exercise Physiology, and Mrs Karina Liles, Scholarly Teaching Fellow in Clinical Exercise Physiology, in the Charles Sturt School of Allied Health, Exercise and Sports Sciences.

World Osteoporosis Day on Friday 20 October is an ideal time for people to understand osteoporosis and to ensure their diet and exercise routines help to minimise the risks to their health and wellbeing.

What is osteoporosis?

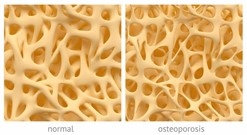

Osteoporosis is a disorder of the skeleton resulting in less dense, frail bones. This results in an increased risk of bone fractures following a minor bump, trip or fall.

While any bone in the body can be affected by osteoporosis, the most common ones are the hip, wrist, and spine. Any fracture can lead to chronic pain, disability, loss of independence or even death.

How is it diagnosed?

Bone density is typically measured using dual-energy X-ray absorption (DEXA) scan. This scan provides a ‘T-score’ which is used to determine bone strength.

Other imaging methods include three-dimensional peripheral quantitative computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

In addition, fracture risk assessment tools consider age, gender, glucocorticoids, and history of fracture to estimate a 10-year probability of fracture.

Who is at risk?

Non-modifiable risk factors are age and gender, with approximately 75 per cent of osteoporotic occurring in people 65 and over, and three in four cases of osteoporosis are in women.

This is because oestrogen has a protective effect on bone, and thus with menopause women lose bone faster than men. Women who have had a hysterectomy or have early menopause are at even greater risk.

Other risk factors include medications, such as corticosteroids and anti-depressants, cancer treatments, and other diseases and disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis, kidney disease, diabetes, thyroid conditions, COPD and asthma.

Modifiable or lifestyle risk factors include excessive alcohol consumption, smoking (doubles the risk of hip fractures), malnutrition (low body weight, underweight and eating disorders), vitamin D deficiency, low calcium intake and inactivity.

Poor bone health can be hereditary, so if a close family member (parents, siblings) has been diagnosed, you have an increased risk of developing osteoporosis.

Symptoms and signs

There are no symptoms associated with bone loss due to osteoporosis, and the only ‘visible’ signs suggesting osteoporosis are a loss of height of four centimetres (approximately one inch) or more and the development of a stoop or hunched posture.

Reducing the risk?

The development of osteoporosis depends on the peak amount of bone attained and the rate of bone loss through ageing. As peak bone mass is attained by about 20 years of age, maximising peak bone mass during childhood and adolescence would be the first step.

It is important to achieve peak bone density in teenage years, and activity levels for teenagers is declining.

Across our lifespan we need to maintain a healthy body mass index (BMI), have a nutritionally balanced diet with adequate calcium and vitamin D and regularly perform weight bearing exercises.

Calcium is essential for building and maintaining healthy bones, with about 99 per cent of the body’s calcium found in our bones.

It is recommended that we obtain our calcium from foods rather than through supplements.

Foods rich in calcium include dairy products, seafoods, green leafy vegetables, nuts and seeds, white meats and fruits.

Vitamin D is needed for the body to absorb calcium from the intestine, and for Australians, the main source of vitamin D is exposure to ultraviolet B (UVB) light from the sun.

The role of exercise in the prevention and treatment of low bone mass

While research shows exercise plays an important role in stimulating bone formation, not all exercise is equal for bone health.

The mechanical loading of weight bearing impact exercise and resistance exercise, especially activities which are completed rapidly or at a high intensity, are most effective in promoting healthy bone cells.

Balance exercises are also very important for people with osteoporosis, as improving balance can reduce their risk of falls and the associated risk of fractures.

PLEASE NOTE: It is strongly recommended that anyone starting an exercise program consult an Accredited Exercise Physiologist (AEP) for an assessment and guidance. For those with a chronic condition, NDIS participants, DVA or private health you might be eligible for free or subsidised services. You can find a list of AEPs in your area on the Exercise and Sports Science (ESSA) website.

The following is a general guide for exercises that are often performed for the prevention and management of osteoporosis. An AEP will provide specific guidelines tailored to your individual health circumstances:

- Weight bearing impact exercise: loading should be vertical and multidirectional, and examples include jumping, hopping, skipping, step-ups and bounding.

- Resistance exercise: usually completed with weights. Resistance exercise should target large muscle groups; examples include weighted lunges, squats, deadlifts, push-ups, calf raises or variations of these exercises.

- Balance exercise: suitable balance exercises will vary for each individual; examples include tandem balance, single leg balance, heel-toe walking, balancing on uneven surfaces or foam mats.

Exercises to avoid with osteoporosis

Individuals who have been diagnosed with osteoporosis should avoid exercises which involve deep forward flexion (bending over) and/or excessive twisting of the spine due to increased risk of spinal fracture. Other exercises to avoid include rowing, sit-ups, and lifting/carrying heavy objects.

Social

Explore the world of social